More than 50 years ago, when most textbooks were written by men, most courses were taught by men, and women’s history wasn’t discussed, the Women’s Studies program began at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.

Just one year prior in 1970, the first women’s studies program in the nation had begun at San Diego State University. A minor in Women’s Studies was approved at UW-Stevens Point in 1976 and has continued to evolve.

“Years ago, women’s studies filled the gap where women’s contributions to society had been overlooked,” said Professor Alice Keefe, current women’s and gender studies (WGS) coordinator and chair of the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies. “Today, an area of pressing concern is gender as a social construct and the limits it creates on how people understand themselves. Students really like the courses, as they speak to the issues they care about, like the rights and dignity of LGBTQ+ people.”

The program was started by Donna Garr, UW-Stevens Point’s equity and affirmative action officer, in the spring of 1971 when courses in women’s history, literature and psychology were offered. A Women’s Studies Committee was formed in the mid-70s, and a minor was proposed.

Now, the minor requires an Introduction to Women’s and Gender Studies course and 15 credits from a list of electives in areas that include English, history, human development, media studies, psychology, religious studies, sociology and political science.

The WGS minor has been coordinated by faculty members from various disciplines. In 1979, Joan McAuliffe, sociology, took on the role, followed by Kathy Ackley, English, in 1982, and in 1992, Nancy Bayne, psychology. The curriculum expanded in the 1990s to provide students with an interdisciplinary perspective in understanding the social and cultural constructions of gender.

Recent coordinators have included Professor Nerissa Nelson, library, and Professor Rebecca Stephens, English. Lauren Gantz, English, will take the role later this year.

The minor has grown from five students in 2020 to nearly 30 in 2023. Students come from all majors and disciplines, from business to social work, Keefe said.

“We are seeing robust growth, rising interest and filled classes,” said Keefe. “I see it as a combination of raised political concerns from Black Lives Matter, the ‘Me Too’ movement and the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and the fact that students are more aware of political and social issues and the need to address them.”

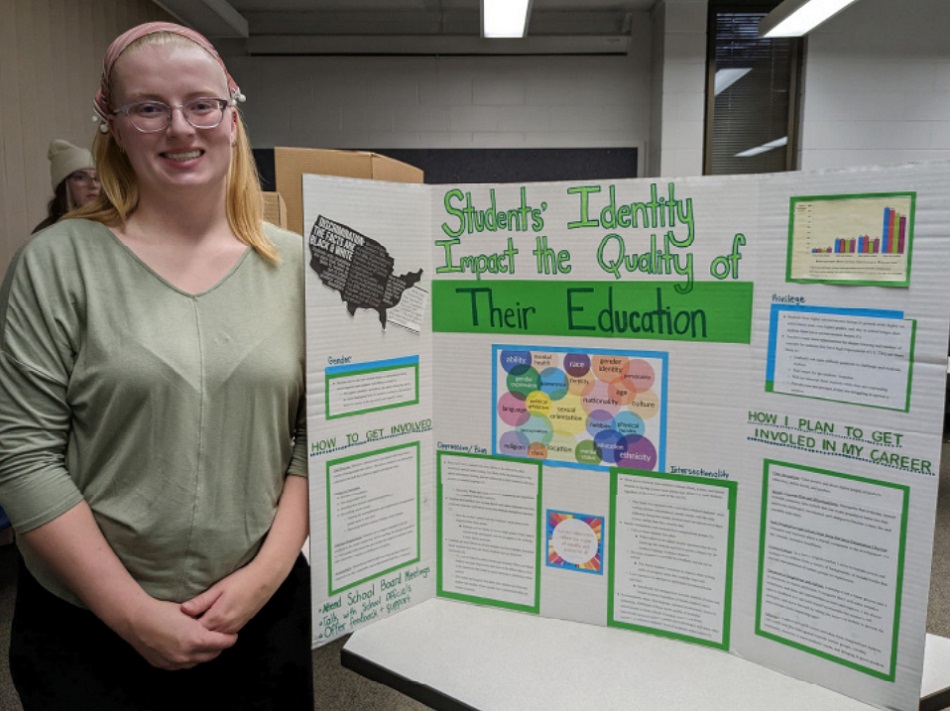

Lindsey Meyer, an English education major, displays her final project for WSG 105, in which students create posters on a topic that is important to them using what they’ve learned throughout the semester.

Lindsey Meyer, an English education major, displays her final project for WSG 105, in which students create posters on a topic that is important to them using what they’ve learned throughout the semester.

The WGS program resonates with Jarita Bavido, Stevens Point, who said she grew up in an environment where women’s voices were not taken seriously. A history, international studies and philosophy major with WGS and art history minors, Bavido said exploring how gender intersects with everything made studies more robust and complete.

“My WGS coursework is the affirmation of my perspective as a woman, that my experience is an asset rather than a liability,” she said. “For those who have never thought about gender, a course like this is a great way to step outside of traditional boxes and broaden your horizons.”

“Our students are not just concerned with earning money, but making social change and making contributions to society,” Keefe said. “People are realizing their rights are not guaranteed, that they have to fight for them.”

Students taking WGS courses learn how to think critically, said Keefe, and how to apply an intersectional analysis to social issues to examine how gender bias and codes intersect with and reinforce race, class, sexuality and disability.

In the introductory course, taught by Stephens, students learn how privilege and oppression can empower or take power away, how different layers of identity, such as race, gender and ability, can intersect, and how to put it all together to create social change.

“Having taught this course since 2000, I’ve seen how the field has changed,” said Stephens. “It’s broadened into a theoretical basis that helps us analyze culture and discuss it in a more intentional way. Students are also more knowledgeable about the ideas we discuss. They are very aware of how these concepts play out in people’s lives.”

“Women’s and Gender Studies goes beyond looking at how women experience the world, but explores how one’s identity shapes their experiences of the world,” said Lindsey Meyer, an English education and psychology major from Auburndale. “The intro course is for everyone and anyone, as the principles discussed apply to all people who seek a more equitable, inclusive and kind world.”

Many graduates of WGS programs go on to work in social services with diverse populations, Keefe said. They choose careers where they are empowered to be nimble and change with the culture, to work with a team and be sensitive to issues in diversity, equity and inclusion. Both Keefe and Stephens say UW-Stevens Point WGS graduates have the ability to see multiple perspectives.

“I hope they make the world more equal for others,” Stephens said. “That they bring equity and justice into everything they do, in whatever workplace they find, so that all voices are heard.”